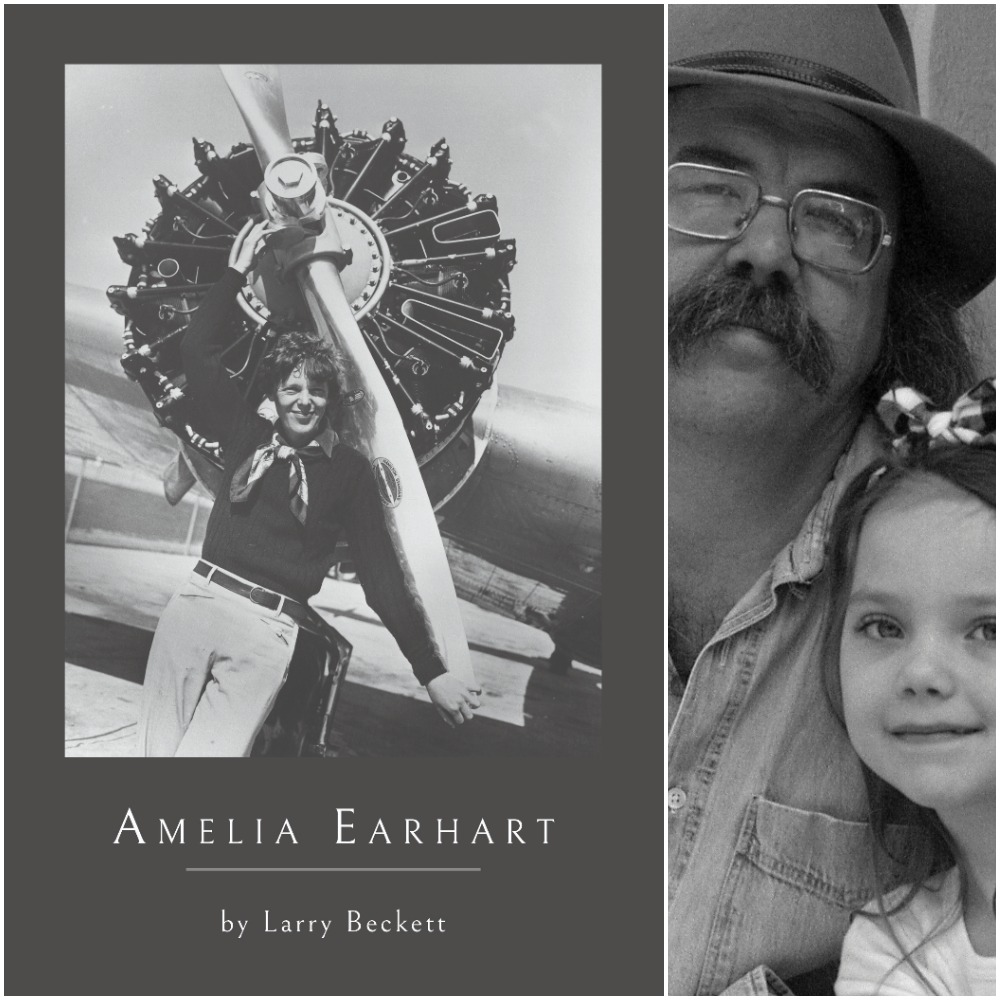

Amelia Earhart by Larry Beckett

$18.99

A ghost-woman’s ruminations on the joys & injustices of her life fly through her memory:

Rhapsodic & reportorial by turns, Amelia Earhart sets the mythological image of the first famous female aviator against her own musings on the facts of her life. The result is an epic monologue that reveals not only Earhart but also Larry Beckett‘s genius for making words dance, for Amelia & for us.

–Alexandra Yurkovsky, poet, critic, author of Wanting

He lifts the wing of that old plane on the ground

so we can see the woman before she takes off.

As he tells us her story, I can feel her on the roof

of the hotel, arms outstretched to catch the updraft.

–Robin Rule, poet, author of Porch Language and Trailer for Rent

Larry Beckett, poet, writer, engages Amelia Earhart, pilot, flyer. Beckett has researched, meditated, mused. He shares his results here, gives us the goods. Using the first-person voice of Amelia herself, often ironic in tone, he makes it mesmerizing. Sea chants. Land chants. Air chants. Who was Amelia? What really happened? She is alive, still flying, imagined and remembered lyrically—seven lines at a time.

–Dan Barth, poet, writer, author of Fast Women Beautiful: Zen Beat Baseball Poems and The Day After Hank Williams’ Birthday

Description

Amelia Earhart

by Larry Beckett

$18.99, Full-length, paper

978-1-63534-635-0

2018

Larry Beckett’s long poem Amelia Earhart is from a sequence called American Cycle, inspired by our history and legends. His work has appeared in Zyzzyva, Salamander, and FIELD. Songs and Sonnets was published by Rainy Day Women Press, Beat Poetry by Beatdom Books, and Paul Bunyan by Smokestack Books.

Paul Wilner –

Paul Wilner, in Zyzzyva:

http://www.zyzzyva.org/2018/11/02/flight-patterns-qa-with-amelia-earhart-author-larry-beckett/?fbclid=IwAR2bCO1D01KgCS-MY0VCvsdIaY368S7Xro618DDwv_uvuSlTC0dktFMBwm8

Stuart Anthony (verified owner) –

It’s a beautiful work. I was struck by how much of a character she was

and how the poetry gave that character new life.

I was next to her in the cockpit, feeling the cold, picking up the old

electric glow of her dials, seeing the broken clouds.

I was next to her on my own horse. I was feeling for her as she dealt

with the pressure of fame. I felt her vulnerability in love.

I stood back as her personal drive filled any room. When a poem holds

you in someone else’s world like that, I can only regard it as a marvel.

A poetic cinema of the mind.

Joe William Taylor –

This long poem is part of a sequence-in-progress entitled American Cycle. As with Beckett’s Wyatt Earp, the reader is advised to read a bit about the life of Earhart, so that many of the poem’s references won’t slip by. Well worth the trouble.

This particular poem accomplishes four wonderful tasks:

First, the entire poem is told by Amelia Earhart’s corpse “unburied, by the wreck / Electra, withering in the salt, -3 miles / altitude.” This narration allows Beckett to clear the air about the many conjectures concerning Earhart’s last flight, since the plane’s wreckage was never found. “Oh listen, the blue flight had no landing, / the worlds are out of balance.” No, she was not taken prisoner by the Japanese and held as a spy. No, she was not released after the war to return as an heiress on America’s east coast. No. No, “oh / for the love of pity, listen, till morning / is here and I go dead.” Not many plays on words in this serious poem, but there sits one: dead, as in radio communication; dead as in a corpse with “coral . . . on my white bones.” The tone lifts in the fourth canto (for lack of a better word) and we relive Amelia’s life as a tomboy, when a family dog frightens the neighbor boys, but young Amelia outs her “hand to / his hackles” and leads him, harmless, to the kitchen. Thereafter the poem entertainingly mixes biographical facts from her personal life with those of her life as an aviator.

Second, throughout the novel a refrain tumbles, repeating the last known transmissions of Earhart and the American Navy crew tracking her. Though not immediately apparent, this refrain begins on the poem’s seventh line, for “Radio Hong Kong” just happens to be transmitting on the short wave frequency of 6210 mhz—one of the two frequencies that Earhart used on her last flight. These refrains, such as “KHAQQ TO LAE AT 7000 FEET AND MAKING 150 MPH,” work much like the “Honest Iago” refrain in Othello, or the witches in Macbeth. They keep the ending in front of us at all times—in this case, Earhart’s crash and death in the Pacific. The refrains come on faster as the book continues, giving urgency to the reading of the poem, nearly working as a plot device in effect.

Third, the ambition, the pride, the fear, the desires of Earhart are fully realized throughout the poem as Beckett relays snippets of her life, her loves, her obsessions. Earhart’s adventurous streak started early and continued. She’s nearly killed when a bobsled runs beneath a dray horse’s feet. She cajoles World War I pilots to teach her to fly. She puzzles her cousins by hopping a fence rather than walking through in a ladylike fashion. Starting on page 46, there’s a very fine five-stanza listing the many adjectives the press applies to Earhart: “”Why am I a chalkboard on which they love / to scrawl adjectives? They call me simple, complex, thorough, grand, pioneer, above / my age . . .” These simple adjectives continue for 31 lines. As Blake insisted, “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” Her listing them reveals her frustration at being seen in simplistic terms, not the least of which is “a female Lindbergh.”

Fourth, this long poem is very much—and rightly—a celebration of feminism. On Earhart’s first flight with a barnstormer she had to be accompanied by a second man: “Who’s this? / —He’s flying with us. –Ah; why? They grin / until I catch on: they think I’m a woman / and frail, I might crack up, into hysteria, / jump, oh and the man’s there to be my hero: / —I’ve been around aeroplanes, and I’m cool; / —Sorry, lady, if he don’t go, you don’t.” Or at an Air Rodeo: “You race? —I guess I can . . . / —Oh, he’ll do the flying, you just ghost it, / and land, the lady winner. —No.”

So. A sixty-page poem about Amelia Earhart, a poem that at times has the intensity of a stage play or a novel, a poem that illustrates an important character in a completely compassionate and convincing way, and a poem that elevates womanhood through its narrator. When the newspaper headlines read, “Girl Crosses the Atlantic,” the poem’s persona wryly comments, “I was 31. They can handle girl, get anxious / at woman.” Indeed.