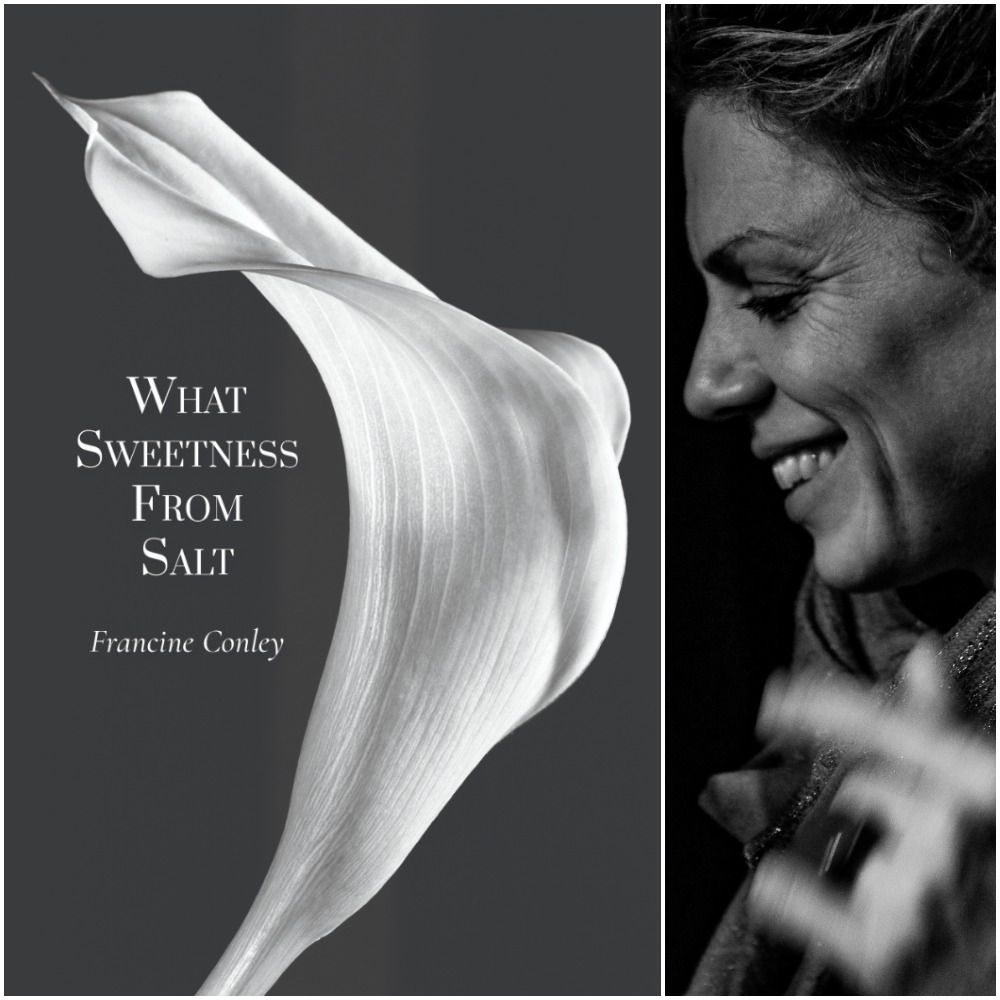

Francine Conley writes with a raconteur’s wit and craftsman’s ear for the frisson between words. In What Sweetness from Salt, Conley weaves the ekphrastic and allusive with her personal mythology, the result of which has a propulsive narrative spine. These poems grapple with the inherited burdens of family and the lovers, cities, and heartbreaks they lead to. Conley’s poems demand we stay porous, desirous, and flawed: which is to say, human.

–Stephanie Danler, essayist and author of Sweetbitter

Francine Conley is a sage soul whose richly powerful collection What Sweetness From Salt absolutely wrecked me in the best way, reduced me to a sobbing, open-hearted mess. These poems are so smart, witty, and incisive, and yet the deep gazing both inward and outward, the introspective deep knowing, I almost had to lie on the floor I was hurting and healing so hard. At every turn, I’m impressed by the fluid movement, how Conley places the glass darkly over a mother’s psyche, shining it over the mess of life, the mother’s life—revealing not a binary but a blurring, showing how “There is no better loneliness than a mother’s love.” She writes deftly and achingly of girlhood, motherhood, rife sexual relationships, and the feminine body and its cultural history of being policed, all in such starkly clear lyric, like glass, breakable. Perfect and breakable. This collection’s syntax and sounds, imagery and wit, thoroughly delight me even as it tears me open, exhibiting such exquisite nuance, maturity, wisdom, and play, as in the following passage, which will stay with me as salt sweetening on my tongue: “In time bitch / stuck in my throat like a bone. Stayed like salt / on my tongue. I used to think it tasted different / in every country. In Switzerland salt tasted thin, almost sweet. In Germany; like cake.” Oh, read for yourself, the sweetness this collection engenders.

–Jenn Givhan, award-winning author of Girl with Death Mask and Rosa’s Einstein

“Say a word like bitch and you’ll be cleaned out,” begins this masterful book about women, mothers and our difficulties finding meaning in a world that values neither. These fierce voices do not worry about propriety so much as they fight to salvage a self who can love in spite of it all. From the Midwest, to western Europe, from a child’s eye-view to that of mature motherhood, the poems in What Sweetness From Salt move us through all the ways that we are “a frightful expression of ourselves.”

–Connie Voisine, author of The Bower and Calle Florista

Nathan McClain –

The title of Francine Conley’s beautiful debut, What Sweetness from Salt, presents its reader with what, initially, seems a strange oxymoron. Salt, of course, flavors, or accentuates flavor. Salt preserves. In fact, it has numerous uses—but sweeten? How to make logical sense of that? Conley’s speaker might simply respond, “I swallowed all of it”: The good and the bad. Trust. Disappointment. Sadness. A father’s infidelity. A mother’s loneliness. “Swallowed all of it,” until her “lips, like memory, / are stung alive”. And memory, the past, are only the beginning of what her speaker must stomach, must negotiate, in poem after poem. But Conley’s speaker does more than simply look, or look back, her speaker carefully watches, sometimes as if “all I can do is watch,” the way Elizabeth Bishop might watch, or like a passenger in her own narrative.

At turns ekphrastic, richly detailed and finely crafted, What Sweetness from Salt explores a speaker’s broken family dynamic and how that past, that memory, informs all within the speaker’s present life and gaze, often consisting of visual art and literature. One turns to art for any variety of reasons. Some for aesthetic pleasure, others for art’s ability to deepen our sense of the spiritual or metaphysical. Some seek to create space and opportunity for reflection or contemplation. Some rely on art’s power to console. Though what is one to do if art is unable to console, to provide resolution, to correct a thing? When art is proven to be limited? How do you then reconcile loss, failure, or disappointment? Conley’s poems do not attempt to use art as a deflection from lived experience. Rather, her poems embrace experience, regardless of how painful, and still seeks to address one of the central questions that haunts the collection: how does one hope, which is “such an old thing” anyhow, “after [or in the face of] so much loss”?

Conley doesn’t provide easy answers. She doesn’t do the emotional heavy lifting for her readers. In these poems, she takes a hard look at the self and the paradoxes of our humanity in a world just “waiting to be noticed,” and she details the “beauty in not / knowing,” in “believing the lie”. In these poems, she presents a speaker cursed with looking— both “seeing” and desiring to “be seen”. But how to say it? And “does what we say come out how // we want?” Even so, What Sweetness from Salt is saying it, in an attempt to “season / the world into something we’d consume”.

Kerrin McCadden –

Praise for WHAT SWEETNESS FROM SALT

Does the slippery title of Francine Conley’s remarkable debut collection of poems, What Sweetness from Salt, promise sweetness, or does it ask rhetorically for the impossible? In poems both lush and devastating, Conley hovers between the two. These poems are gorgeous depictions of loneliness and isolation, reaching back toward a withdrawn mother and a father too much in the world, and pressing forward into adulthood with “hope, / like a roach on the wall.” Even when the poems respond to works of art, the viewer does not arrive at easy enlightenment. Again and again, art leads inward to losses and abandonments and men whose collective distance compounds. Images from the natural world—bats, “stranded jellyfish,” a “mangy pigeon,” a vandalized elephant skeleton, “a motley of bees,” and flies—gather to illustrate a loneliness that manages, somehow, to be beautiful. These poems are overrun with pain and struggle and loss, but not once did I want to stop reading. Conley’s sharp eye and quick mind carry and carry and carry. There is an intimacy here, too, love and generosity. As I read these poems, I forget these stories are not my own. With a keen eye and resounding musicality, Conley buoys her reader. These poems are rich with surprises and threaded through with fire, their speaker ablaze with moving forward, each poem mouthing “I—Am—Here.”

Kerrin McCadden

Author of Keep This to Yourself (Button Poetry, 2020) and Landscape with Plywood Silhouettes (New Issues Poetry & Prose 2014) — http://www.kerrinmccadden.com

L.A. (verified owner) –

In psychiatry they say that what you choose to see is often what you are programed to see. It is also true that what we see is what we choose to see, in a given painting, for example, or situation, or person. In at least seven of the poems in “What Sweetness From Salt,” Francine Conley explores relationships, and connections or lack of connections, and especially our relationships with ourselves, by describing paintings (and art installations) in ways that reflect a psychological moment experienced by the “I” narrator. In “The Blue Fountain Sings” after De Chirico’s “The Poet’s Pleasures” (also translated, on the web, as “The Delights of the Poet,”) she, with such deft deflection, turns us from the painting to experiences with a lover, a trauma, her father, and back to the painting, as though the painting was essential to understanding this particular loss, recovery, and sorrow, never stated, just experienced. She does this again and again with the paintings, making them come alive with personal, mysterious messages about our lives. As though that which is around us can inform, amplify, or alter our stance toward our experiences. In addition to the collection of ekphrastic poems, there are poems “after Proust,” and “after Baudelaire” and moments in other poems informed by a mother wanting to re-experience her own pain through her daughter by seeing performance art, and a father who paints, which brings the method of ‘seeing a life through paintings’ extra potency. A narrative of trauma weaves through these poems, and also what trauma brings—awareness, compassion, heartbreak, and defenses, told through the mother/father archetypes, and the idea of art as transformation, survival as an art form, and art as a way to see into one’s soul.

E. (verified owner) –

Yes, Francine Conley’s WHAT SWEETNESS FROM SALT explores the well-trod terrain of motherhood and domesticity, but, Reader, watch her mouths, “I was born open- / mouthed” (from “Stray”). Conley is a poet with a ravenous appetite for protean imagery that collapses sense and time—resisting easy calculation—as in these lines from “The Bat Situation”: The sound of each letter spreads over my tongue / the way as a child I watched my father, / a painter, stretch white canvas taut / over each hammered wooden frame. No, Conley doesn’t simply stare at the frame, but she steps into, and through, the frame. This is apparent when Conley engages with the ekphrastic mode in poems like “An Old Woman Cooking Eggs” and “The Wedding Portrait.” With all of that said, what thrills me most about this book is the audacity of the poems’ structures; complex, and often multiple, narrative structures get couched within the frame of one lyric moment—as is the case with the poem “Windows.” WHAT SWEETNESS FROM SALT is a dynamic feat which warrants multiple readings.