Description

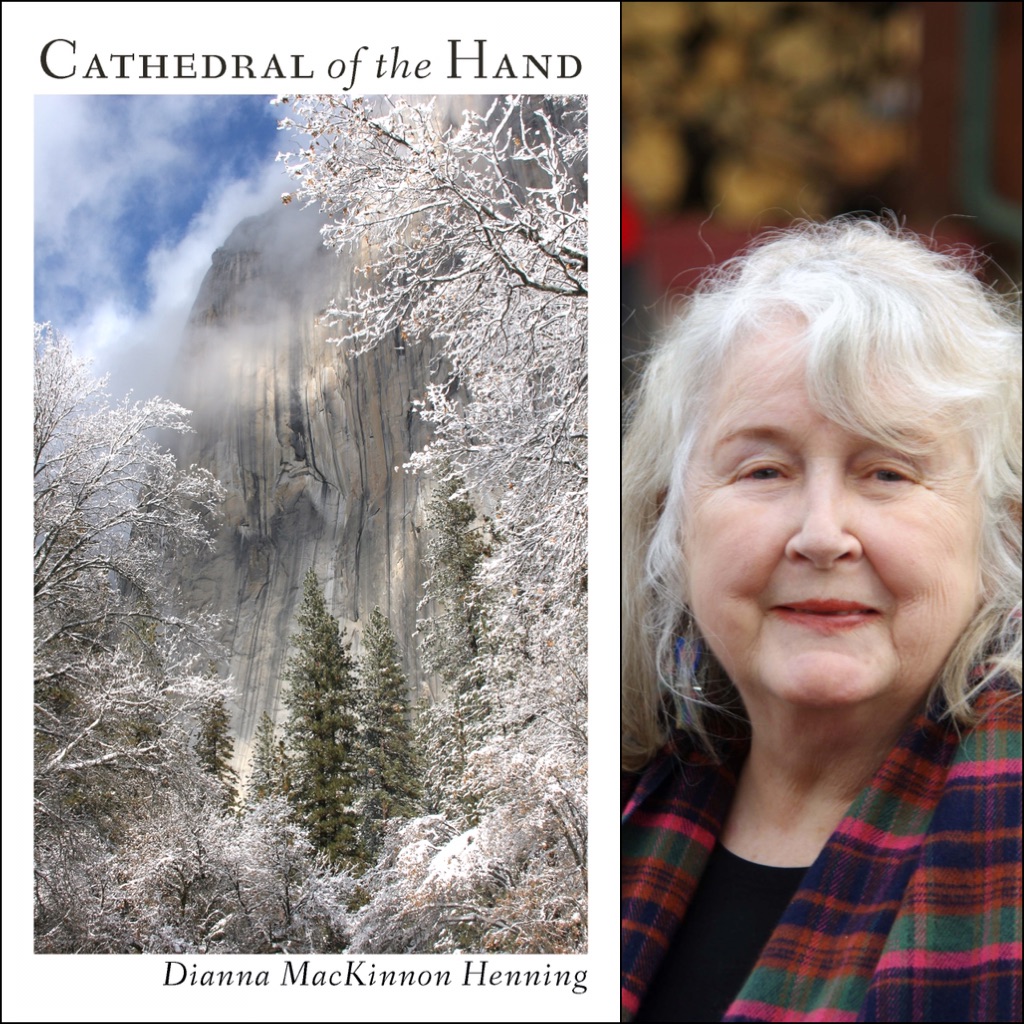

Cathedral of the Hand

by Dianna MacKinnon Henning

$14.49, paper

Ms. Henning was born and raised in Vermont. She holds an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Published in, in part: The Kentucky Review, The Main Street Rag, Crazyhorse, The Lullwater Review, California Quarterly, Poetry International, Fugue, The Tule Review, The Asheville Poetry Review, Clackamas Literary Review, Red Rock Review, South Dakota Review, Hawai’i Pacific Review and The Seattle Review. Twice nominated for a Pushcart. Won fellowships to Bread Loaf and Dublin Writers’ Center. Finalist in Aesthetica’s Creative Writing Award in the UK, published in their Annual 2014.

Dianna taught for California Poets in the Schools, and through the William James Association’s Prison Arts Project. She also participated in a California Council for the Humanities Stories project and taught creative writing at the Susanville Rancheria where she worked with Maidu, Pit River and Paiute writers. She has been a recipient of several California Arts Council grants which allowed her to teach creative writing at Folsom Prison, the Stockton Youth Authority, Stockton, CA and at Diamond View School in Susanville CA.

Dianna lives in Lassen County on six acres with her husband Kam and her malamute Sakari. She facilitates The Thompson Peak Writers’ Workshop in Lassen County.

E-Address: gammonmackinnon@diannahenning.com

Rating: ***** [5 of 5 Stars!]

Bob Stanley –

Cathedral of the Hand by Dianna Henning (Finishing Line Press, 2016)

Review by Bob Stanley

One reason I read poetry, and I suspect many of us do, is that the best poems reveal the character of a poet – another human being – in a profound way. We can come to know someone we’ve never met in person through poetry. When we read a new book by Gary Snyder, say, or Jane Hirshfield, we’re touched by individual poems, but through the calculus of the collection, we see them in their world, whether it be their reality, their dreams, or something in between. By reading poetry we find new friends. In this time of quarantine, I’ve found poems ever more nourishing in this way.

Dianna Henning’s Cathedral of the Hand (Finishing Line Press, 2016) performs this welcome trick for me. Through these poems I come to know someone who finds transformation in her surroundings – the high, arid beauty of remote Lassen County, California. Henning’s poems peer into the ponds, fields, and sky of a rural life to reveal who she is, what she loves, how her mind works. And while the subject matter shifts from natural to human relationships, from childhood to adulthood, the same wise voice, deep and insistent, rings. There’s a connection with nature that suffuses the book. “Before rising into the foliage of my life, I was honey. (“Clover”)

Henning’s language – sensory and unflinching – grabs the reader right away. The first few poems remind me of H.D.’s poems – short, clear images that speak for themselves. In “What She Tells Them,” a poem about Jane Kenyon, the poet attests

She speaks of the sea,

of depths beyond belief,

of shrouded bones,

and words diaphanous as air,

of star-catchers in their bright tunics.

Words are connected to nature, “diaphanous as air” here, and the poet strives to connect again and again. In her closing poem “At the Center,” the poet tells us

“I want to become the air the fox breathes.” Rather than longing for the past, there is longing for connection. The short poems convey this longing, this connection through concrete image and action. The poem “Once,” begins with a nugget of memory,

We scudded smooth-bellied stones across the lake,

counted their skips and starts to see who won.

Time passes, skips away quickly in the middle stanzas of this poem as the two characters grow old, but the stone returns at the end, concrete and symbolic at once.

But memory is a dicey thing

a stone that sinks

to settle where it can’t easily be seen.

Reading Henning’s transformative poems reminds me why I write, what it is I’m trying to do when I write; she sharpens my ear, my pen. With a little of the Zen of Gary Snyder, and the sense of wonder conveyed in Mary Oliver’s poems, Henning witnesses animals in their element: a buck deer passing by during a drought year, dogs barking under the moon, a trapped hummingbird freed by her husband. Each piece reveals a moment, and each moment fits into the whole. She chronicles a chorus of crows that fill the background of a human funeral with their chatter. She writes about hands – the hands of an older woman that “are slipping into mine,” and “the hand that touches the things of this world/and transform them” from the title poem “Cathedral of the Hand. There’s humor here, and hints of uncertainty:

What the hand would do for world peace

Is seldom mentioned

in the larger colony of hands.

but ultimately reverence and wonder:

The hand could be an angel if it tried.

See how the fingers open like wings.

So many of her lines ring like bells, her clean, clear diction is the work of a master.

But it’s a modest voice, a voice that always includes what Jane Hirshfield says a poem needs: emotion, intellect, and physicality. Henning doesn’t write a lot about poetry per se, but she clearly understands that a craft requires both work and alchemy in “Needing Bread.”

There’s no way to explain

the mastery of bread-making.

It requires one straighten the spine,

push down what’s risen.

At the end, we feel we’ve walked alongside this poet; we’ve smelled the lilacs in a dry country, been included in her journey of heart and mind. I’ve only driven through the town of Janesville once; some might call it a remote corner of California. This collection of poems reminds me that I love remote places like this, places of reflection. Reading Cathedral of the Hand makes me want to go there, to breathe it for myself, and if she had time, I’d like to drop in on the poet and have a cup of tea. For now, in this time of separation from others. I’m glad I have her poems. They create a small transformation; they bring us together.