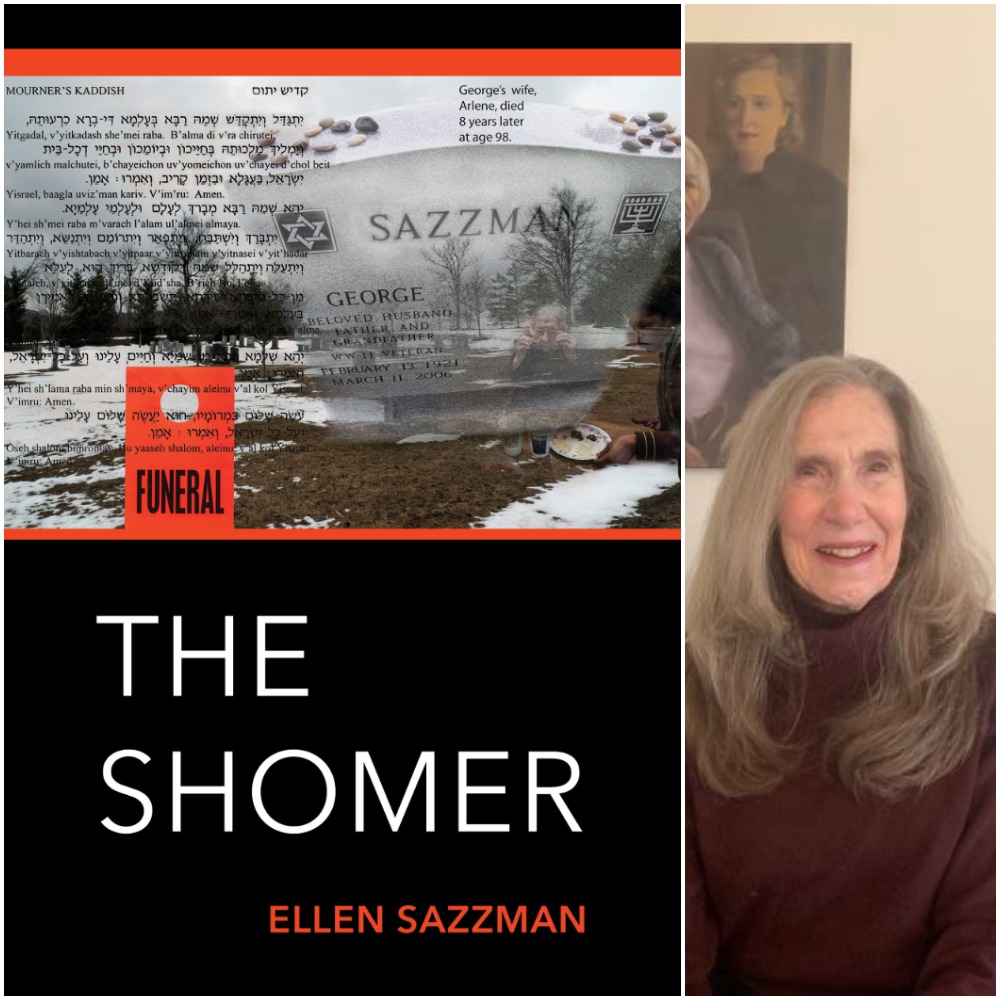

The shomer is one who plays the role of watchman in the Jewish traditional shemira, the guarding of the dead. In the old tradition, all shomrim sit and protect the body which cannot protect itself. They guard against desecration before burial. Without the presence of the shomer, the dead are still subjected to the judgment of God, though they lack the agency to act and resist such corruptions of the body. Thus the shomer is the advocate and protector of those who can no longer protect themselves, but one who also gains a special glimpse into the liminal, a witness to what happens in the space between life and burial. In Ellen Sazzman’s moving, revealing, truly dazzling poems, the symbol of the eponymous shomer is used in sections that watch over and witness the passing of three sorts of life force: the parents, the old traditions, and one’s own body. The brilliance of that: that the poet is also the witness to her own corporality, and that she is charged to step away from the body, so to speak, to keep its vigil. I can think of no better metaphor for the role of poetry, and there are few who do this work more elegantly and more truthfully than Ellen Sazzman. She is a writer who has lived in those “neither-worlds,” one who knows about advocacy and the power of exacting speech, and, while this book is a debut, it has been shaping itself a long time. I hope The Shomer is the first of many such books, the first of many such guardianships. Her work holds, seemingly effortlessly, the balance of authority and tenderness.

–David Keplinger, author of six poetry collections, most recently The Long Answer

The Shomer opens on an elegiac note, but make no mistake; this collection teems with life. Intimate, honest, and wryly funny, these poems travel the journey of miles and years, asking us “Who doesn’t hunger, / wouldn’t hunt for more”? That hunger is both metaphoric and literal, as seen in the second section’s one-two punch of “Jewish Girl’s Guide to Guacamole” and “Brisket Wars.” From Cleveland to Cape Cod, from Mexico City to Saint-Malo: complementing Sazzman’s rich imagery and sense of place is her easy touch with the sonnet, the ghazal, and other formal traditions. Having followed this poet’s work for years, I’m delighted for others to join me in appreciating her discerning voice and artistry.

–Sandra Beasley, author most recently of Made to Explode

The Shomer: What an apt title for Ellen Sazzman’s book, which acts as a guardian/custodian of so many deeply important things. Family, the body, love in all its guises, lives lived and deaths experienced — this accomplished collection takes us from Bernini to brisket, from lemon to Leica, in a vast sweep of personal and cultural history. Formally adept, the poems gracefully skirt the line of the subversive: “Eve, Pandora, Lot’s unnamed wife, / curious women who dared to open themselves / to the forbidden with a taste, a touch, a twist.” Lovely sonic patterning and images from all the senses resonate and stay with the reader, an old perfume bottle whose “glass is cloudy / but luminous, a filament of moon flickering.”

—Moira Egan, author most recently of Synæsthesium

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.