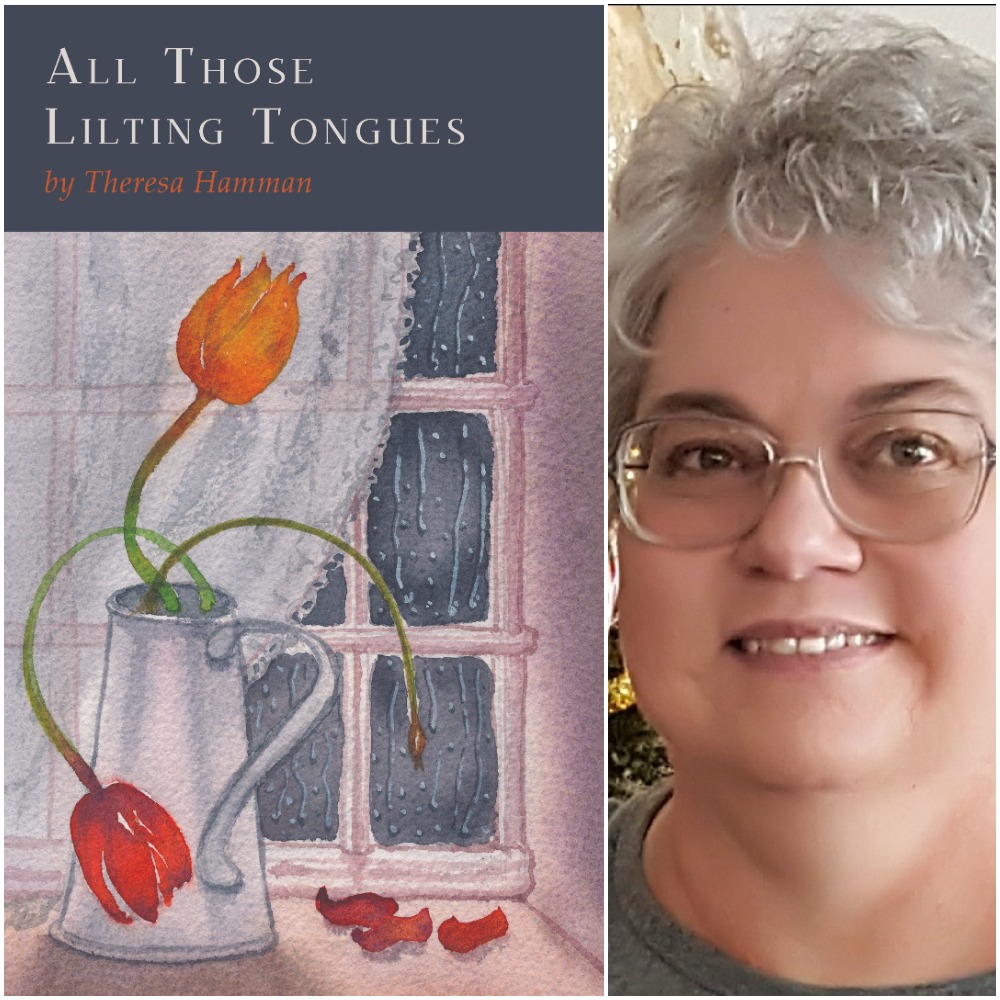

“The masterful, taut poems in Theresa Hamman‘s All Those Lilting Tongues speak the varied dialects of grief and longing. Yet they do so with such rawness, such vulnerability, we can scarcely turn away from the power of a woman over and over baring her wounds and reclaiming her life, especially at this cultural moment, as she stitches back together the “skins of rain/collected long before fires . . . creating new rivers.” Through her own “remembered agony,” as Donald Hall once called it, Hamman reminds us that the common language of poetry can both name past pain and heal it at the same time.”

–James Crews, author of Telling My Father

“The beautiful, brisk poems in All Those Lilting Tongues ache hard under the pressure of heavy ice and snow. Yet, on the banks of Hamman’s loss-frozen lake, we sense a soul warmed by survival, by belonging to the land and family. Drawing deep from her body and breath, she gifts us this miraculous cycle of grief-songs, hard-earned-wisdom-songs, rebirth-songs. A rare gift indeed that moves us beyond language, to the planes of pure emotion and pure art.”

–Justin Hocking, author of The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld: A Memoir and Reclamation: Essays

“ ‘I don’t know / what I feel like doing / all these places don’t open until nine,’ writes Theresa Hamman near the end of All Those Lilting Tongues. That wink of self-irony and humor characterizes many of these carefully made, gestural poems about human endurance at the margins. By turns harrowing and grief-stricken, Hamman’s work is also as kind as it is wise. ‘The lucky people are the ones,’ she writes in another of this fine chapbook’s poems, ‘who / not only win the weekly shoe lotteries, but / also the annual lottery of socks.’ We too are the lucky ones, who hold this book in our hands, and luckier still to discover the many pleasures in its pages.”

–David Axelrod, author of The Open Hand

“In these precise and hungry poems, we are given haunted and important anatomies. Anatomies of bodies that break and lust and die, of interior spaces carved by memory and its revisions, and of what is rendered by the power of witnessing without looking away. Even when the beer hits the wall, the tree bursts into flame, and the ghost insists you are not among the dead. This collection is rich with details of the real, while moving into the vast spaces of the yet-becoming. A brave, dark singing.”

–Jennifer Boyden, author of The Mouths of Grazing Things and The Declarable Future

Nancy Dafoe (verified owner) –

All Those Lilting Tongues by Theresa Hamman

Review by Nancy Dafoe

Could there be a poetry chapbook more apt for the moment and Me, Too movement than Theresa Hamman’s All Those Lilting Tongues? Hamman’s taut lines, “all you/ ever do/ is show me/ how your subzero/ lips curl/ around your canary/ teeth/ as you gnaw/ on an old steak bone” reveal menace and bullying while the woman in the poem “listens/ to the sing-song voices of our children/ chanting Frost” in “Winter People.” “It’s cold” in the house of this poem and in the relationships we decipher in the compressed lines of Hamman’s poetry. That chill extends over much of the verse in which, “It’s a waste of magic to wish someone dead.”

Perhaps the most poignant juxtaposition of violence and love is found in the poem “What Was Breaking” in the crystalized lines, “And the beer can explodes/ against the kitchen wall, / directly above the baby.”

Beautifully understated and metonymic, Hamman’s verse powerfully and uniquely suggests rather than states: “A neighbor’s truck/ ignited for no reason” in her poem “Aftermath: Divorce Finalized.” Anger has disappeared from the verse, however, as we sense the poet’s persona has pulled back, no longer a participant but, rather, a witness and chronicler of life.

Beneath the threat of violence is the sorrow over what was lost. Loss is a motif that extends throughout the chapbook. From the sorrow expressed in “The Day My Father Died” in which the poet’s persona roams “the cemetery/ searching for the best place, one with a view” to the “room sighing with dust”… “before all this whiting” in the poem “All Hues,” Hamman’s terrain is emotional devastation: “He only tells her love/ is suicide, and she/ holds the note/ he wrote all over her body” in the poem “Love is Suicide.” Even the sunset “has lost your name” in Hamman’s poem “Without.”

There is a rebirth, a hope, but it is not without peril and scars: “a fracture/ one dead eye/ perches on a high/ cliff watches/ the plates shift” in “Rebirth.” New rivers are created but not before “you feel/ the way your back/ fissures open/ blisters—/ oiling out/ all black.”

As we drive away with the protagonist, we can still hear the thunder, are aware of the lightning, before the “lilac blooms blew/ away, before…we laughed/ while the yellow desert ate us.” There is something lost in “Driving the Desert with Zep” but never forgotten: “We knew how to buzz once…before we became sulfured honey.”