Description

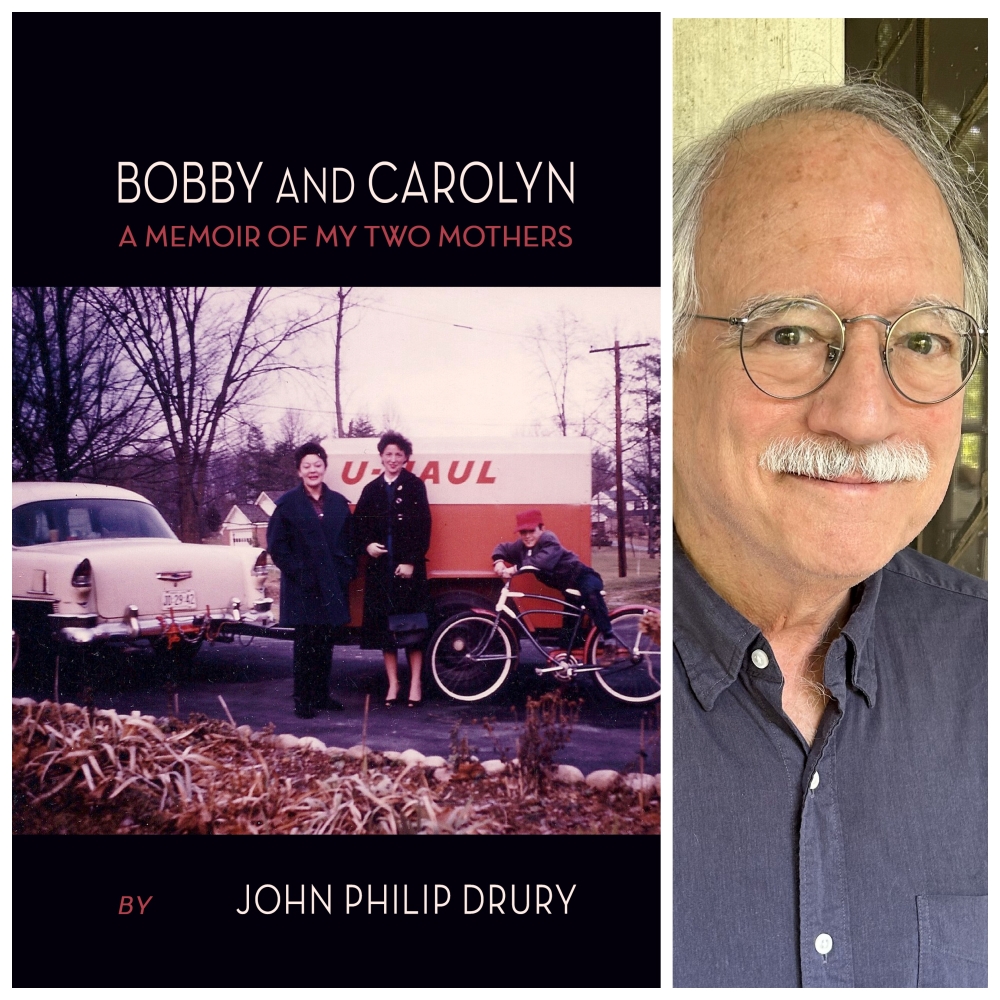

Bobby and Carolyn: A Memoir of My Two Mothers

by John Philip Drury

Full-length, Paper

List: $24.99

979-8-88838-597-5

2024

Bobby and Carolyn: A Memoir of My Two Mothers focuses on the author’s mother and the “glamorous soprano” who came between his parents when he was eight years old. They both fell in love with her, but Carolyn Long and his mother, whose nickname was Bobby, ended up together, sharing a life and what they secretly considered a marriage, having exchanged vows on a moonlit night in the summer of 1958. This memoir celebrates the do-it-yourself union between two women: a housewife who became a bank teller and a professional singer who became a voice teacher. It endured until one partner’s death in 1991—memorialized by the cemetery plot they share, with their names engraved on opposite sides of the tombstone, just like the names of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Their life together was turbulent, partly because of their volatile personalities (and it took volatility to make such a leap of faith into forbidden love in the Fifties), partly because of prejudice against same-sex relationships, so they had to call themselves “cousins” in order to rent an apartment or a house together. Although the author grew up with the two women and considered Carolyn more of a parent than his father, he didn’t discover the true nature of their tumultuous relationship until both women had died and left clues for him to find in their diaries and notes.

John Philip Drury is the author of six collections of poetry: The Stray Ghost (a chapbook-length sequence), The Disappearing Town, Burning the Aspern Papers, The Refugee Camp, Sea Level Rising, and The Teller’s Cage: Poems and Imaginary Movies. He has also written Creating Poetry and The Poetry Dictionary. His awards include an Ingram Merrill Foundation fellowship, two Ohio Arts Council grants, a Pushcart Prize, and the Bernard F. Conners Prize from The Paris Review. After teaching at the University of Cincinnati for 37 years, he is now an emeritus professor and lives with his wife, fellow poet LaWanda Walters, in a hundred-year-old house on the edge of a wooded ravine.

Ellen Brown, Nonfiction Editor –

Interview by Ellen Brown, Nonfiction Editor

(Published in DELMARVA REVIEW, Volume 15, 2022, pages 106-111)

Brown: “Full Moon on the Water” is an excerpt from your book-length memoir, Bobby and Carolyn: Two Women with a Boy in the 1950s, which is currently seeking a publisher. Would you like to talk about your book, your inspiration for writing it, and how “Full Moon on the Water” fits within the book’s larger context?

Drury: When I was a graduate student in the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins, I wrote a pair of poems about my mother’s childhood, but only one of them, “The Dry Goods Store,” made it into my first full-length collection, The Disappearing Town. Over the years, I wrote other poems about my mother, her partner Carolyn, my father before and after the divorce, and (in one case) all three of them: the mistitled pantoum “Storm on Fishing Bay,” whose real setting is Wingate on the Honga River, one of the estuaries that flow into the Chesapeake. Many of my poems were attempts to recover my home territory of Dorchester County on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, and I actually focused more consciously on place instead of people. But my drafts had a strong narrative thrust, so they drew in characters, often members of my broken and revised family.

I had always wanted to write fiction but felt intimidated and stymied by the need to fictionalize (although I did it often in my poems). I became interested in the possibility of writing narrative nonfiction in the 1990s, and I came up with a handwritten list titled “Voice Lessons: Autobiographical Essays,” which included “The Idylls of Childhood,” “A World of Embarrassment,” “Basic Training,” “Language School,” and “Voice Lessons” (which I ranked number one, as the piece I wanted to write first), all followed by parenthesized lists of subjects and details to include. I hoped that each fragment or image could open up a “lane to the land of the dead,” as the “crack in the tea-cup” does in W.H. Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening.” At the time, however, I didn’t get around to writing any of those essays, but I did jot down several pages of notes based on my mother’s recollections of her childhood. And that’s really a continuation of the journals I had kept since I was 19, sometimes regularly (during, for example, basic training at Fort Dix), but often sporadically. Although I did mine the quarry of my journals for details in poems I was writing, I longed to write longer narratives in prose.

Several years before my mother died, I moved her from Cambridge to Cincinnati, and that proximity allowed me to ask her questions and jot down notes. She knew I was gathering material for a book about her and Carolyn, and dialogue about that research project is how “Full Moon on the Water,” the last chapter in the memoir, ends. But in that note-gathering phase, I still imagined that the memoir would focus on all three of my “parents” (Carolyn, my mother, and my father) and the importance of music in their lives, so the working title was Voice Lessons for the Dead. The first full draft was around 350 pages long, but I’ve gradually cut it down to 234 pages. My father became the odd man out, the dispensable part of what the song “Tom Dooley” (a hit single when my original family broke up) calls the “eternal triangle.” Most of the chapters and scenes about him, as well as a chapter about the Kingston Trio’s song, ended up on the cutting-room floor.

In drafting poems, I almost always use a pen, but one of the alterations in my writing process that made narrative nonfiction possible was typing the drafts of chapters on a laptop. Since I use only my right index finger for typing, the tempo of my composing was more andante than presto. I’ve done it that way so long, however, that I’m fairly quick, and I’m in the habit of revising as I go.

As that list of possible “autobiographical essays” reveals, I was thinking of writing about both my childhood on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and my experiences in the Army (“language school” being the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, where I studied German). I decided to divide those aspects of my life into two memoirs, one focusing on my mother and Carolyn, the other titled The Bad Soldier: A Picaresque Memoir of Enlisting in the Army to Avoid Being Drafted during the Vietnam War.

Brown: As an accomplished and award-winning poet, you’ve authored four full-length poetry collections, two books on the craft of poetry, and your poems have appeared in numerous literary journals. “Full Moon on the Water” is a memoir, but it also contains references to poetry, including a lyrical love letter from Carolyn to your mother presented in the form of a poem. Can you talk a little bit about how writing poetry informs your prose? And do you come from a literary background?

Drury: I come from a musical background, not a literary one, but it helped my verbal development that I spent a lot of time in Episcopal churches, attending Sunday school (which my mother taught), taking confirmation classes, and singing as a boy soprano in the choir, where I noticed that the music of the Book of Common Prayer paralleled the hymns we sang: “We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts. But thou O Lord have mercy upon us miserable offenders.” I’m quoting that from memory, so it may be slightly inaccurate.

The love letter from Carolyn to my mother is formatted as she wrote it on note paper, which I wanted to preserve in the quotation. The narrow margins forced unintended line breaks, as in the fascicles made by Emily Dickinson, so that one of her most famous hymn stanzas looks like this:

Because I could not

stop for Death —

He kindly stopped for me —

The Carriage held but

just Ourselves —

And Immortality.

I wanted Carolyn’s words to be not just her final letter but her last song.

When my friend Stephen Kuusisto began writing his first memoir, Planet of the Blind, prose poems served as his gateway to narrative nonfiction: “The book’s first draft was essentially a daily notebook of prose poems written over the course of a year” (“On Writing, Blogging, and Waking Early”). I have approached my own narrative nonfiction partly from the perspective of poetry but also from a habit of making journal entries—and even from the way I composed recommendation letters, taking detailed notes so I could quote the spoken remarks of colleagues and students.

Brown: In your book, Creating Poetry, you write about using memory as a source of poetic inspiration: “Memory plays a multiple role for the poet. It supplies the kindling—and often the fuel—for the imagination. It is often the subject of poems”1. It seems that poems and memoirs are similar in that they often start by recalling specific moments or aspects of a writer’s life. Is there a reason you choose a memoir to write about your mother and Carolyn’s relationship rather than a collection of narrative poems?

Drury: I didn’t begin writing my two memoirs until after my mother had died, but I knew that I wanted to write them both in prose, like nonfiction novels, and not as sequences of poems. In fact, the last chapter of my Army memoir, “Seeking Asylum,” was preceded years previously by a sequence called “The Refugee Camp” that first appeared in an issue of the now defunct Open Places, guest-edited by Carolyn Forché, and eventually grew to 48 sections that were published in my third book of poems, The Refugee Camp. The prose chapter is novella-length, and I relished the opportunity to expand, develop, explain, ponder, and include more information. The music in poetry and the music in prose strike me as palpably different, and I like how those differing cadences move through time. I listen to both as I’m writing.

Brown: Memoirs have the potential to shed light on lived histories and experiences that are entirely different from our own. “Full Moon on the Water” is about discovering that your mother and Carolyn secretly exchanged wedding vows in 1958, a time in history when same-sex relationships were legally and socially persecuted in the United States. Sixty-four years have passed and same-sex couples in all fifty states can now lawfully marry, yet gay rights remain an issue. Is there a larger cultural conversation you hope your memoir will be a part of? Is there a universal experience to which you hope it gives a voice?

Drury: When my mother died in 2007, the barriers to same-sex marriage were still intact and cruel. That was still true when I finished the first full draft of the memoir in September 2011. What really propelled a liberating change of attitudes and then laws happened to be Vice-President Biden’s generous off-script comment, regarded by some as a “gaffe,” during Meet the Press: “I am absolutely comfortable with the fact that men marrying men, women marrying women, and heterosexual men and women marrying another are entitled to the same exact rights, all the civil rights, all the civil liberties. And quite frankly, I don’t see much of a distinction beyond that.” One of my goals in this chapter and in the whole memoir is to show how difficult it was, from 1958 to 2007, for two women in love—and how heroic. An epigraph by Adrienne Rich, from “Twenty-One Love Poems” (XIX), emphasizes that difficulty:

two women together is a work

nothing in civilization has made simple

The memoir is essentially the love story of my two mothers, and I think it makes sense (as in Thelma and Louise) to present it by using the nickname and name they went by together: Bobby and Carolyn. It sounds like a fanfare to me.

1 Drury, John. 1991. Creating Poetry. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books.

Kirkus Reviews (verified owner) –

Kirkus Reviews

BOBBY AND CAROLYN: A MEMOIR OF MY TWO MOTHERS

by John Philip Drury ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 9, 2024

Drury’s memoir recalls his life with his mother and the “glamorous soprano” who became a second maternal figure to him.

The author spent his early years in Cambridge, Maryland. His father, Phil Drury, was a bank teller and parttime tenor in the church choir. His mother, Carolyn (aka Bobby) Bayly Drury gave up her bank teller job when her son was born and became a full-time homemaker, supplementing the family income with her dwindling inheritance. Drury was in grade school when he first met Carolyn Creighton Long, the woman who would come between his parents. She was an opera singer who had just moved back to Cambridge after studying grand opera in Italy for two years. She returned to great acclaim, but she was emotionally broken—according to Drury’s mother, Carolyn suffered a nervous breakdown while abroad. No longer able or willing to pursue her musical career through touring with musical production companies, Carolyn began offering voice lessons in Cambridge. Phil approached her for singing lessons in 1956. It is not clear just when a relationship began between the two Carolyns, but by 1958 Bobby was smitten and Carolyn Long had become a fixture in the Drurys’ lives. After Labor Day of that year, Phil Drury left home in the middle of the night, moving to a small Greenwich Village apartment in New York City where he hoped to find a better job and pursue a career in singing. Carolyn moved into the Drury house, effectively becoming the author’s second parent. Drury summarizes the turbulent events in one of his many “Disclosures,” intermittent entries in the narrative that review and interpret events as he remembers them: “My father was the odd man out in this trio, matched up against two Carolyns, ultimately a bit player. By leaving, he left them with each other, now a duo, and he left them with me.”

Drury’s account makes for a complex, tempestuous, and, at the time, socially unacceptable love story. It is a tale of passion that alternated between great expressions of love and devotion and screaming fighting matches, especially after heavy drinking. The relationship lasted, on and off, for 30 years, until Carolyn Long’s death. Indeed, it lingered on after her demise—in one especially poignant vignette, the author describes visiting Carolyn Long’s grave for a memorial a year after she died; he walked behind the headstone and discovered that his mother had had her own name engraved on the back of the stone. The two women would be forever united. A published poet, Drury has a keen ear for the tempo and cadence of engrossing prose. There is one exception, when he dwells on lengthy recitations of Carolyn’s numerous performances during the 1940s and early 1950s. These may be of interest to fans of classical music, but they are not described with any musical texture and, notwithstanding the inclusion of well-known luminaries with whom she sang, readers unfamiliar with the specific pieces listed will likely become disengaged during these passages.

An intriguing, tender, and elegantly written tribute to the author’s two mothers.

— Kirkus Reviews

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/john-philip-drury/bobby-and-carolyn-a-memoir-of-my-two-mothers/