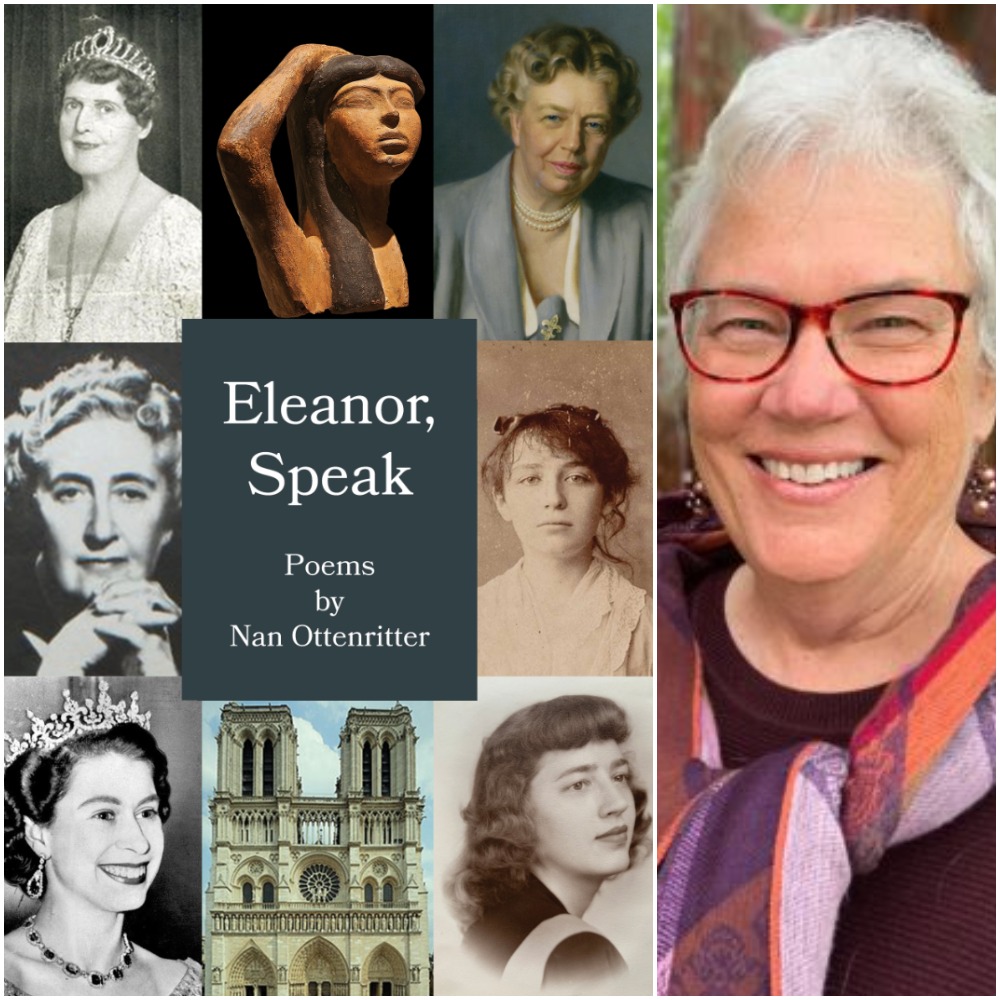

Eleanor, Speak by Nan Ottenritter

$14.99

Nan Ottenritter’s poems have guts. They dare to confront the evils of our time, to insist on history too many of us have forgotten, to face our mortality, and to fly as lyrically as Baryshnikov without fear of falling.

–James Penha, editor of TheNewVerse.News

Through a prism of artistes, heroines, and mother figures, Nan Ottenritter peers behind the drapes of history, grief, age, and survival itself. Familiar figures Agatha and Eleanor come to life from dusty pages, and we find new humility and understanding from Florence and Camille. Little Lincoln’s mother catches us at our core, and the author’s own battle with cancer catches at our breath. It is a book that celebrates the female, that alchemical mix of perseverance and grace with the potential to “raise a daughter full of sparks dying // on their way to the heavens.” A book that will make you want to call your mom.

–Joanna Lee, author of Dissections and founder of River City Poets

Eleanor, Speak celebrates women, among other things—from Camille Claudel to a greasy-spoon waitress, from an oncology nurse in Boston to Notre-Dame de Paris herself. Nan Ottenritter roams history and observes life with equal parts intelligence, compassion, and restless curiosity. In her acknowledgments she thanks “the written and spoken word,” noting “what an excellent puzzle it is to translate life into symbol and sound.” Indeed—and how exciting it is to watch this poet emerge from her chrysalis, stretch her new wings, and take dazzling flight.

–Douglas Jones, author of Songs from Bedlam

Marjie Gowdy –

Review: Eleanor Speak, Poems by Nan Ottenritter

Finishing Line Press, 2021

If only every woman, young and old, could read Eleanor, Speak, Poems by Nan Ottenritter. This magnificent collection of poems touches upon the views of both women of history and women imagined and met during Ottenritter’s lifetime. Each work explores the emotional depths of its subject and brings to every personality a magical reinvention by the poet. A mother, reading this book, would nod in shared pain at the stories of grief and sudden loss. The woman on the train would read into the poems her own aspirations and disappointments. The young girl, seeking heroines, would find them here, whether in a tattooed waitress or a sculptor who flew and stumbled.

This reader, a third generation of mystery aficiandos, learned that her own hero, Agatha Christie, kept writing well into old age even as her faculties were possibly dimmed by dementia (“The Seventy-Third Book: Letter to Agatha Christie”). There is something in the creative soul that demands a way out, as Ottenritter writes in her quartet of poems about the doomed sculptor Camille Claudel: accused of appropriating the work of her lover Rodin, Claudel defended herself by saying she had “too many ideas rather than too few”.

It is in daily interactions that Ottenritter also draws inspiration. In “Little Lincoln,” she writes if a young mother with few means could name her baby Lincoln Alyosha (adding in a nod to the tale “something like that”), then “all…will be well.” Ottenritter reflects on a brilliant protégé in “Educating Rachel”:

“What do I want for her? To taste paradise, drink deeply of love,

trust her voice, and treasure her creations.

I want this to happen, yet fear it may not.”

Ottenritter brings fresh insight into the lives of well-known women. The impression of Florence Foster Jenkins in a recent film trailer is of a gadfly with Hugh Grant at her side. In “Verdi Would Have Wept,” the story is both grand and sorrowful, yet with a hopeful end note: “no one can ever say I didn’t sing”. In the title poem, “Eleanor, Speak,” the poet writes also as an activist wondering how the grand First Lady would have reacted to the dangerous tumult of these times: “Eleanor, what would you do…wear a pussy hat, pen a poem?” In “Notre Dame,” that most elegant of inanimate ladies is remembered in the aftermath of the 2019 fire:

“…glorious rose windows, sonorous

pipes and bells,

all in peril.”

Grief is the through line in much of this collection, a raw and unforgiving grief that is felt in the soul of every woman – and man. In “I Know How,” the nurse assures a family forced to face life’s end for a beloved brother. Both the dying brother and the nurse on duty suffer from cancer. Horror and grief are expressed in “Making of an Enemy,” as a young teen’s menstrual cycle and pregnancy are tracked by a past presidential administration. “The Mothers of the Movement squint in TV lights” in “The End of This,” a poem, like “Keeping Count,” that stirs our collective grief at the violence of this time. As well, “After Dessert” recalls the unspeakable dread of that sudden phone call reporting a young person’s suicide.

Ottenritter has an ear for the silence in conversations and an eye that translates movement and hesitation into words. Her poems such as “Metallic Transfer Cases” and “The Gesture” show humanity at its best in noble and humble ways.

Yet, overall, a sense of joy abounds in soft brush strokes throughout the collection. Ottenritter is a poet in the purest sense, a teller of tales and recorder of the little moments. “When My Mother Met the Queen” and “mom’s cast-iron skillet” are simply delightful, as is “Downsizing”:

…Champagne! A toast!

The party is wonderful. You boxes, you knew all along!”

Open this lovely book, and join Camille Claudel as she rides through the City of Lights over 100 years ago (“Camille Bicycles through Paris, Spring 1887). Hear the “cobblestone-clatter”, watch her “French braid unbraided”, riding “silt- and sand-dusted” and topless through Paris. Sit at the café and observe with Ottenritter the magic of an earlier time as yet another courageous woman reviled in her day rides toward the glory of a happier future.