Description

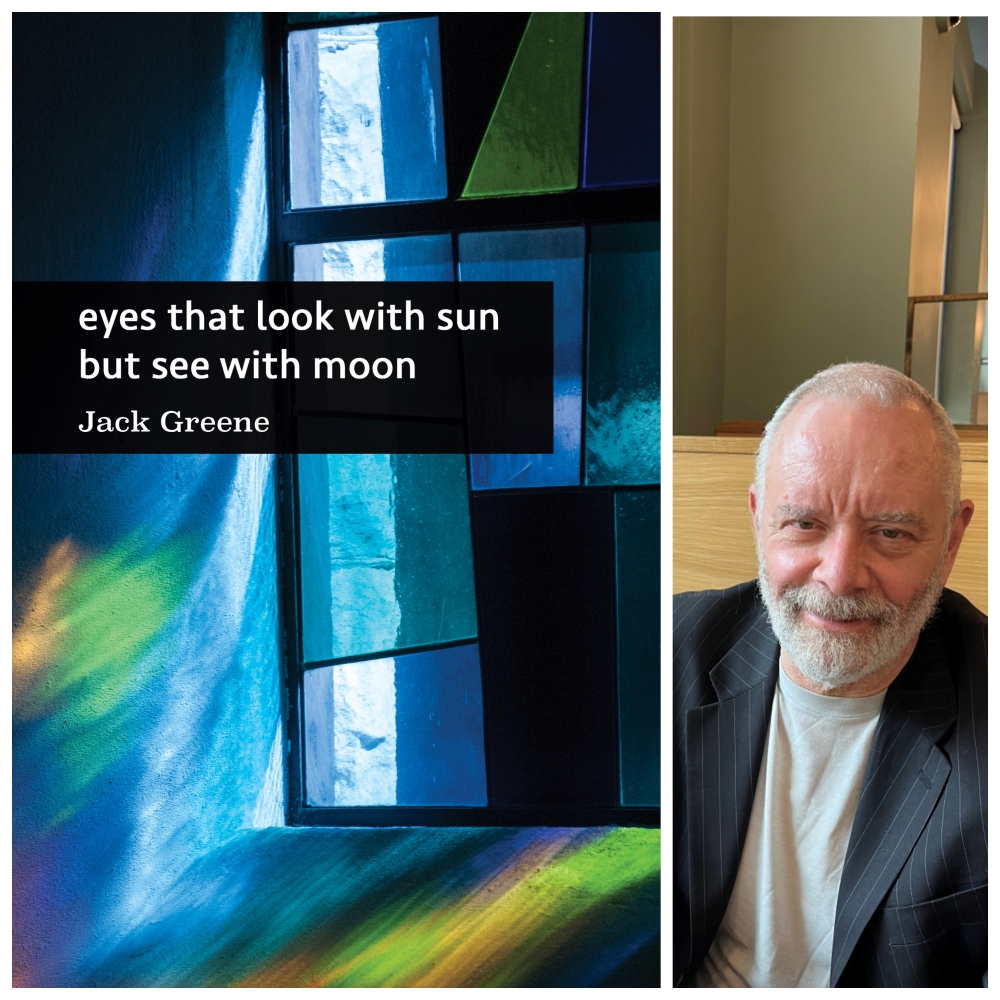

eyes that look with sun but see with moon

by Jack Greene

Paper

List: $17.99

979-8-88838-624-8

2024

“eyes that look with sun but see with moon” moves the reader through rooms of Vermeer to atomic fall out shelters to dioramas of taxidermied deer, finally arriving where it started: in light. The experience of the poems is an intimate, internal gallery, one that merges words and images and light into a new gravitational pull, each in and of its own frame, and all a part of this life, this planet.

Jack Greene is a poet and photographer. His poetry has been published in the Liliput Review, not enough night, Bombay Gin, Mungo vs. Ranger, Rattapallax, and the Sextant Review. He holds a MFA in Writing and Poetics from Naropa University, as well as BA in English Literature from the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a past recipient of a Colorado Council on the Arts Poetry Fellowship and served as a poet-in-residence for the Colorado Council on the Arts. He has taught poetry and creative writing workshops and courses in the Front Range. His photography has been exhibited at Naropa University, the Boulder Jewish Community Center, and the University of Colorado, Boulder, and can be viewed at jackgreenephotography.picfair.com. He lives in Longmont, Colorado with the writer and performer Lisa Trank.

Kevin Maines –

https://northofoxford.wordpress.com/2024/11/01/eyes-that-look-with-sun-but-see-with-moon-by-jack-greene/?fb

Review By Michael T. Young:

There is a richness and complexity to eyes that look with sun but see with moon which other poets would need a full-length collection to accomplish, but Greene lands perfectly in the compressed space of a chapbook. Like Blake or Grossman, Greene never talks down to his readers but treats them as equals in a world of profound intelligence, bringing them on a journey of metaphysical redemption.

The opening several poems ground us in a perspective of nature and imagination, the former being what the world of man is disconnected from and the latter being a natural thing and by which the artist may reconnect us to nature. So, while we are told that imagination is:

.

. . . an instinct

in which the world

becomes itself again

(“Untitled, Parenthetically, pg. 2)

.

We are also told of the speaker approaching the glass to look closely at a stuffed deer in the Natural History Museum, that he is:

.

danger’s last image

approaching

the glass

(“Simulacrum at the Natural History Museum” pg. 3)

.

It is between these two points that the collection evolves toward a confrontation with death, loss, and grief, which is to say, connects with the tradition of the pastoral elegy in a highly nuanced way. The approach of the speaker to the deer in “Simulacrum at the Natural History Museum” is echoed in another early poem “Vermeer’s Aquarium.” But here the speaker approaches a work of art, and doing so:

.

Approaching the canvas

we find certainty

in the light—

.

like Proust in his cork-lined room

like Cornell in his glass cases

like deer at a lake at dawn

(pg. 5)

.

The certainty found in the work of art is compared to other works of art and to an image of nature, reinforcing the assertion that imagination is an instinct, a way for the artist to answer the disorder and loss experienced in a world disconnected from the natural order of things. Or, in other words, the divide between man and nature is bridged by imagination. This becomes key to the consolation found in the face of loss and grief, a cycle not only of artistic creativity but the generative process that is life itself, and which we connect to through love and the new life it brings into the world. This is threaded through the collection by a wonderful metaphor in the thread Ariadne gave Theseus to find his way out of the labyrinth. But it appears variously as “a single thread of moonlight,” a wedding veil that “unravels into a beam of light,” a “chord of flesh,” even a

.

golden-thin

salt-engendered

fry

a thread

of antiquity

(“Where French Fries Come From,” pg. 15)

.

Such a pedestrian thing as a french fry becomes a symbol of a metaphysical force binding us to the cycle of life. In this instance, the eating of the french fry also becomes an unspoken communion that provides again the certainty we don’t have consistently in our disconnection from the earth, but here in this is a

.

a slight yetcertain trace

of brown—

.

a footnote

to the earth

.

pure joy

cherished bliss

for those of us

deprived of myth

(“Where French Fries Come From,” pg. 15)

.

One can’t but relish the irony here in a collection that underpins its metaphysics with such an ancient myth as that of Ariadne, a collection so modern supported by a story from ancient Greece. And we are all Theseus within this story, journeying deeper and deeper into the labyrinth, which is the pain and suffering of living.

As the collection shifts from childhood memories to the death of a father in “Kaddish,” and the death of a friend in “Dans l’ensemble” we also see how art and the generative process of creativity in all forms is the thread leading us out of the labyrinth of human suffering. In “Kaddish” itself—while the most common of the five variations of kaddish is a mourning of the dead—Greene connects more to the tradition of the pastoral elegy in the evolution of his poem, leading us from mourning to consolation, and a reconnection to nature but here, through poetry or “song,” which is, since imagination is an instinct, is not different from nature itself.

.

where one

belongs—

.

song

.

house of hill

sky and sea

.

song

.

sun and moon

leaf on tree

.

song

.

father’s foot

a constant

.

song

.

even now

with him

gone

.

song

.

father lived

and died

in

.

song

.

sing on

old man

sing on

(pg. 20, 21)

.

While this is an elegy to the poet’s father, it’s difficult not to hear those last lines as an encouragement to the poet himself to go on, to endure in the production of song or taking part in the life of generations, falling in love, having children. And one sees this in the poems that follow. As the poem “Time” which is a love poem simultaneously to the poet’s wife and unborn daughter

.

as now

time grows

round

inside you

(pg. 23)

.

And this, directing us through the final poems, is the thread through the labyrinth that is a human’s experience in time, the suffering that is the human condition. The penultimate poem “Prayer to Ariadne,” grounds us again in the collection’s unifying mythology or metaphysics. Then the final poem, an epithalamium, returns us to the symbolism from earlier poems where

.

what mattered

was the man

before her eyes

.

and the knowledge

that the light

in his came in

part from hers

.

eyes that look

with sun but

see with

moon

(“Coda: Sun and Moon, Moon and Sun,” pg. 31)

.

There is a deepening here of the tradition of the donna angelicata, the divine figure of spiritual perfection that guides the poet, such as Beatrice for Dante in the Divine Comedy. But here consummation or union is necessary to connection to the natural world, the healing of the rift, and the way out of the labyrinth of loss and grief that is time.

.

One of the extraordinary things about this collection is that within all this depth and complexity, there is also playfulness and irony. One has a sense that even in the face of all this weighty matter, Greene has the ability to enjoy himself and bring us with him. What eyes that look with sun but see with moon accomplishes is similar to Blake’s illuminated books but without the illustrations. It’s a collection that calls us back to find clarity and consolation in its vision.

.

You can get the book here: eyes that look with sun but see with moon

.