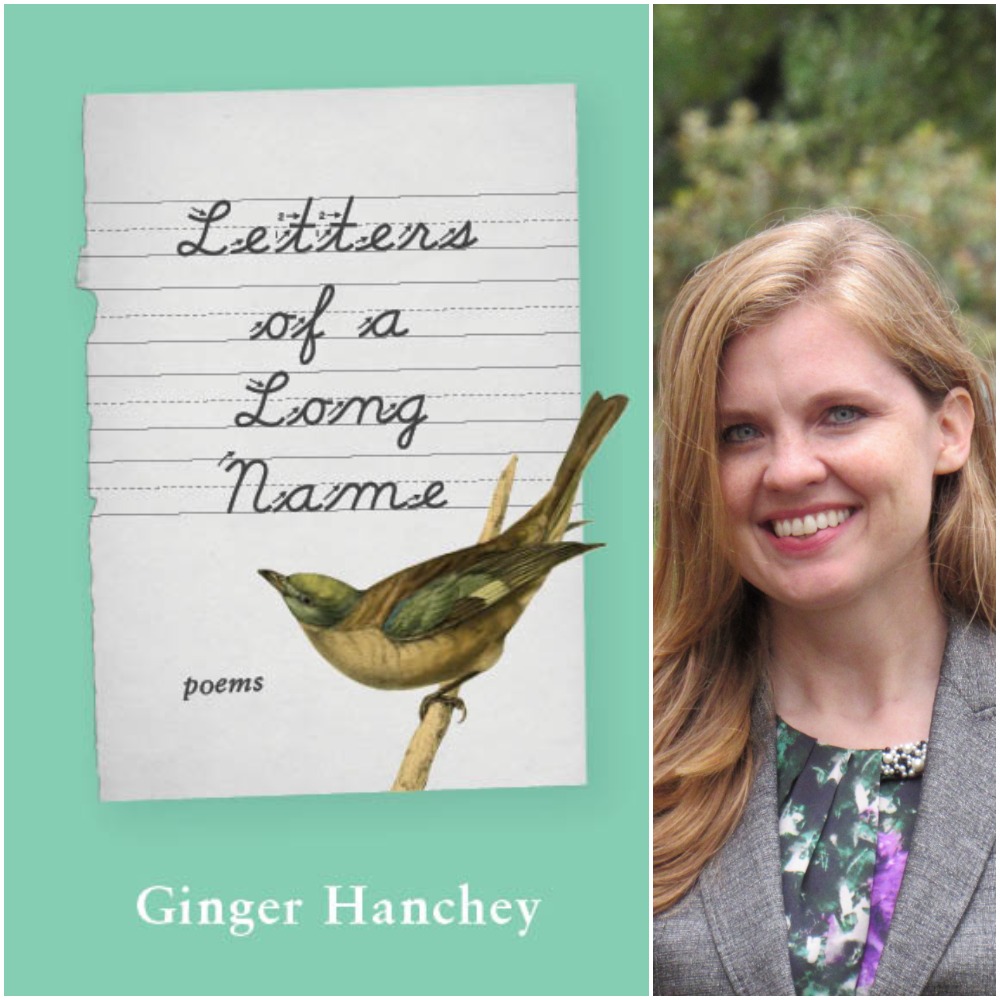

To surrender one’s child—to thriving, to failure, to a life beyond the parental “maker”—is perhaps the business, the labor, of all poets. But in the raw, precarious, “naked lullabyes” of Hanchey’s stunning book, the stakes of doing so are brought into fierce, urgent domestic intimacy as the mother of a critically endangered NICU-tethered second son copes not with metaphorical invention but with its very real and grave consequences. With Penelope-like steadfastness, the speaker in these poems measures out her family’s imperiled days, months, and years of crisis not in Prufrock’s coffee spoons, but with a mother’s expressions of stock-piled breastmilk, faith, and prayer, kept alive by poetry’s vital abeyance and creation’s ultimate reward.

–Lisa Russ Spaar, Director of Creative Writing at the University of Virginia, author of Orexia

Ginger Hanchey’s narrator spends a long time in an NICU and then a lifetime recalling the grim circumstances of her son’s birth. From the window of that children’s hospital she sees “a vast parking lot, then a freeway, / and further still fields that are fallow / now with fall.” It, too, is a grim landscape, but “further still” is one with promise of growth. The book is as elegantly constructed as that sentence, for the narrator, too, will hope, seek faith, find deeper self- knowledge. Hanchey’s writing broke my heart, then put it together again.

–Kurt Heinzelman, Co-Founder of Bat City Review and former Director of Creative Writing at the University of Texas at Austin, author of Intimacies and Other Devices

Ginger Hanchey’s Letters of a Long Name is animated by precisely rendered juxtapositions. The stark beauty of the natural world is glimpsed through the windows of the NICU where the speaker’s son is gravely ill; appeals to god for comfort are met by silence, as in the remarkable poem “Epiphany,” in which the speaker recounts how she “prayed / again my wordless, dry-heave / of a prayer for him to live / but there was no echo, no / bottom to the well where / my coin would land and / sound back up hope.” I admire these poems for how they resist an easy narrative of redemption: though the child survives, and we see his mother’s love for him through her keen observation (“the wetness of his hair evaporates, quick as childhood,” she notes in a closing poem), her faith is not returned wholecloth, and the child’s illness heightens our awareness of the precarity of such intense love. And yet the poems are alight with bodily joy, as in the closing of “On the Brazos,” where, watching her sons, the “two miracles” she nearly lost, play, “happiness spreads beneath my skin like a bruise.”

–Nancy Reddy, 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, author of Acadiana

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.