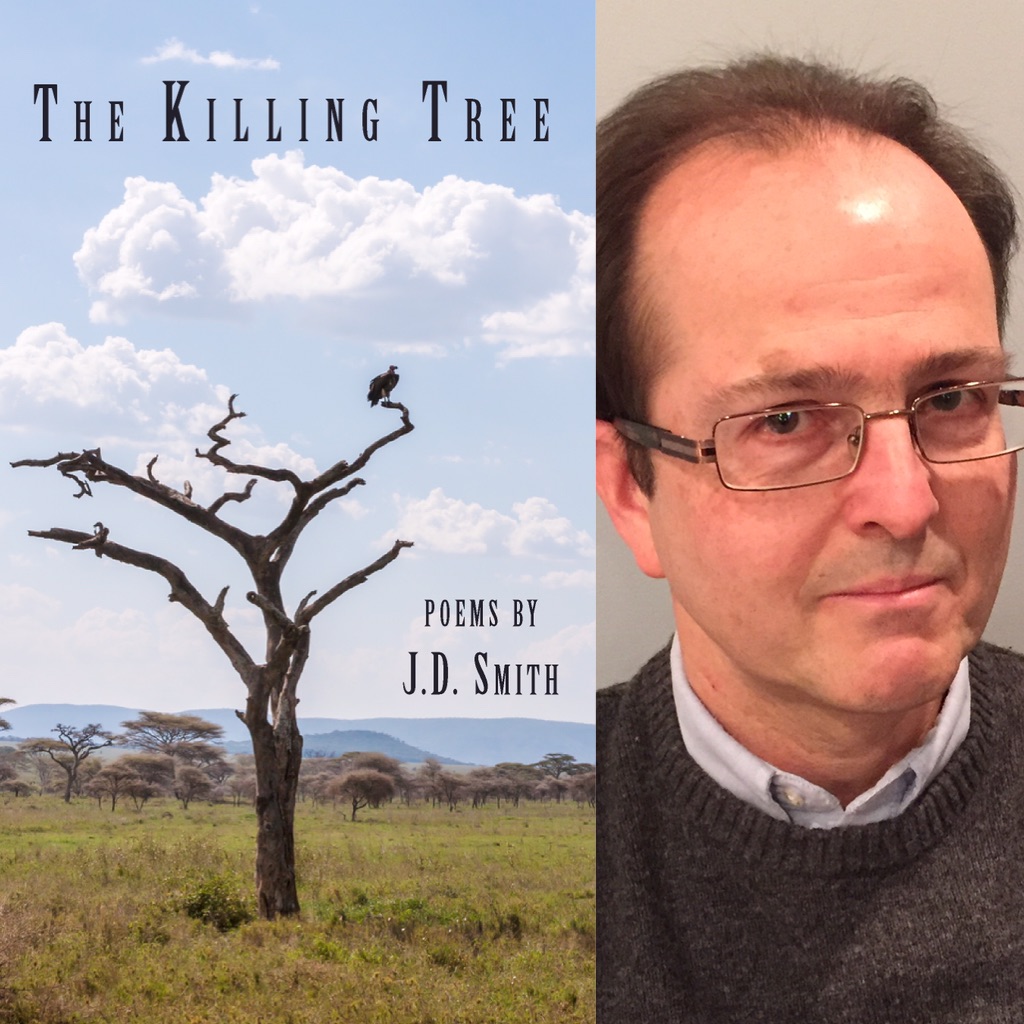

J. D. Smith’s poems are full of wit and doughty faith. As he says in “Upon a Birth,” we enter this world without, as far as we can tell, having any say in the matter; and the nature of things and our own limitations thwart our attempts to achieve fullnesss of being. Yet he also movingly observes that we persist in seeking goodness, truth, and beauty—narrowing in the process “the distance from the real to the ideal.” The Killing Tree is a triumph of life and art.

–Timothy Steele

In his collection The Killing Tree, J. D. Smith deploys a vast array of poetic forms—including the kyrielle, sonnet, rondeau, rhymed couplets and quatrains, ghazal, ballade, triolet, monorhyme, villanelle, blank verse, and free verse—in investigations of personal crises and relationships, and musings on daily routines and failures of idealism, justice, and government. The poetic forms themselves exert their subtle pressure, condensing the carbon of experience to a gemlike polish that is by turns lyrical, musical, cynical, satiric, or moving. The wry humor of comparing a feeding frenzy at a koi pond to the trade show the speaker has just left (“Botanical Garden”) or of presenting the flip side of Dana Gioia’s “Pity the Beautiful” in a celebration of the ignored and undervalued (“Envy the Dutiful”) contrasts with the restrained grief of a sonnet on the loss of a child (“Elegy”) or a scathing portrait of scholars who smugly frame policy debates, but “step around the beggars stretched outside” (“Consultative”). From the personal to the political to the philosophical, there are poems here to suit a wide range of readers.

–Susan McLean

The poems in J.D. Smith‘s latest collection, The Killing Tree, exhibit an ear fine-tuned to the musicality inherent in a wide variety of received forms, including the sonnet, villanelle, ballade, rondeau, heroic couplet and triolet, as well as a keen eye for detail with which he depicts the many aspects of our common humanity.The exquisitely heart-rending sonnets, “Elegy” and “Drunkard Watched from an Upper Floor”, the humorous and self-deprecating ballade, “The Cool of ’94”, the incisive “Fragment from Zeno” and the trenchant “Missing a Vigil” are but a few examples of Smith’s excellent delineations of the broad themes of life, death, despair, time and social injustice. “At a Bistro”, a tour de force of wit and craftsmanship, itself is worth the price of admission. Part 3, where the title poem appears, is Smith’s scathing indictment of the status quo (“Century of Ideas”), and, in a series of pieces culminating in “Along the Potomac”, he excoriates the rampant political corruption of Washington, D.C. The repeated item on Smith’s prologue poem, “Agenda” is his desire “To be a string played by the wind”, that is, to act as an Aeolian harp, essentially acting as an instrument capturing the chaos of the wind’s vortices and translating them into song. The Killing Tree has done just that.

–Catherine Chandler

The herb rue, while bitter on the tongue, has medicinal qualities, and in some cuisines adds flavor to dishes. Rue, meaning regret or sorrow, is—Merriam-Webster tells us—etymologically unrelated to the herb. J.D. Smith’s The Killing Tree is flavored with the sorrowful, second sort of rue, but like the first kind, it has soothing properties and a flavor one easily begins to savor. How does this book belong in a review of light verse? For one thing, the noun that most easily comes to mind accompanying the adjective “rueful” is “smile,” which is the expression I surely wore while reading his book. For another, Smith’s excellent formal control is used in service of illuminating the absurd, pricking the pompous, and pouring sugar in the engine of the daily grind. Smith offers in his latest work a perspective that fearlessly explicates the world’s sorrows and shames while also loving it—and making us love it—for its imperfections.

First of all, read this book simply for the lovely, if often sad, poems in it. I won’t go into great detail on these except to say that in the general sense of lightness, Smith’s touch is just that, even when the topics are heavy. “Upkeep,” which compares a couple’s financial precariousness with the beehive that’s attached itself to their window, showing its productive insides, is a rare poem that captures the chronic wear of hardship but without bathos or pity, just with facts. Smith just might be the laureate of the dashed-dreamed cubicle-dweller who is still surprised by ordinary beauty.

There are some truly—though still ruefully—funny poems in The Killing Tree. “Spinoza at Lenscrafters,” for instance, disorients the philosopher (who was himself a lens grinder, and, according to the internet, likely killed by a related lung condition) in a shopping mall. The idea of a painstaking life’s work being reduced to a mechanical hour’s wait among the Sbarros is almost as light as this book gets. But Smith is also, quietly, a fantastic parodist. His “Envy the Dutiful” considers the kids who were likely picked on by those in Dana Gioia’s “Pity the Beautiful,” and Smith decides (rightly, I think) who wins in the end. “The Cool of ‘94″ establishes the unlikely but probably-would-have-liked-each-other pairing of Villon and Cobain and shows the shallowness of our current world’s nostalgia for a time so recent I still have T-shirts from it.

A Washington D.C resident, Smith does not fail to skewer his city’s main industry. For example, “Citizen Vain” is a poem about a yuuuuuge personality very much in the news whom Smith drops neatly into Charles Foster Kane’s psyche. Smith has all sorts of subtle fun with the sexual psychopathologies both tycoons share, including giving feminine end rhymes to lines about virility: “His name writ large on thrusting towers,” and “Fresh wives imported like cut flowers.”

The Killing Tree offers a unique voice, one in which the poety ego is almost completely blocked from coming through. Instead, that random business traveler in the airport bar has his moment, as when contemplating “Monday in Las Vegas”:

Housekeeping finds stray bits of

What happens and stays here:

Pawn tickets and a red chip,

Three shoes and one brassiere.

–Barbara Egel in the Summer 2016 issue of Light.

Rating: ***** [5 of 5 Stars!]

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.