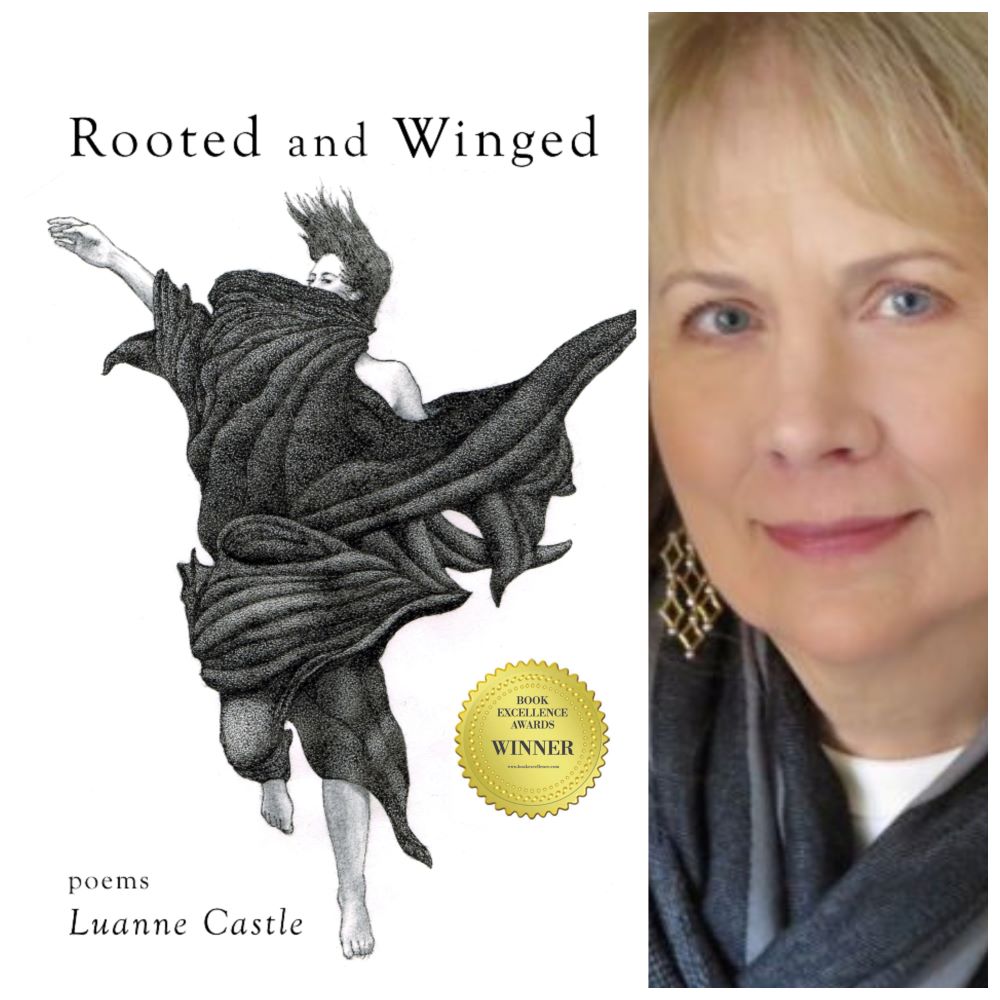

The poems of Luanne Castle’s Rooted and Winged are embedded in land and weather. “Bluegills snap up larvae in slivers of illusory light,” she writes early in the collection, hinting at the sensibilities of the companionable speaker who will usher us through the book. She sees. She is open to the world out there. She calls herself “unknown but solid,” a teller of “tiny limitless tales.” She is engaged in the retrieval of generational memory: “one hairbrush, a plastic ball / a swaying branch, leaves decaying / the insides of my grandmothers’ fridges / bubble and pop into shards of memory / dangerous to the touch,” she writes, enacting the progression from concrete detail to concrete memory to the kind of numinous memory that can be combustible. How rare it is, to discover a writer who notices that “Grandma used to stand under the bulb over the sink that haloed her and pearlized the onions she chopped,” who can bring language to this: “When the last star falls to the others, / it darkens like the hush in a theatre, / a twinkling or two from silence.” There is no arrogance in this book, but there is power.

–Diane Seuss, Pulitzer Prize winning author, author of frank: sonnets, Four-Legged Girl, and Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl

Luanne Castle’s Rooted and Winged is an intimate journey through a topography where home encounters wilderness, and where the speaker must determine what she owes to her children, to aging loved ones, to the land and its wild inhabitants, and to herself. In poetry that reveals the connection between what we inherit and what we leave behind, between what changes and what remains constant, Castle explores the mystery of what happens after a person “survives [her] own birth.” The resulting work is undeniably graceful, compelling, and heartrending. “The way the sun came between me and the water will always seem like an introduction,” Castle writes, as she deftly creates, from the seemingly mundane, “something splendid.”

–Chera Hammons, author of Maps of Injury

Rooted and Winged is a fitting title for this collection of poems that plant themselves in reality but often hint at the surreal. Throughout, Luanne Castle has mastered sound and image: I’ve done my best with feet and fists, my small / lungs blossoming like paper flowers in water… The poem that lingers most for me is “A Year in Bed, with Windows” in which stark details create a palpable intimacy.

–Karen Paul Holmes, author of No Such Thing as Distance.

Carla McGill (verified owner) –

Luanne Castle’s third collection of poetry, Rooted and Winged, is a striking exhibition of poetic intuition and skill. Comprised of forty-four poems and structured in four parts, the poems take readers on a journey through contrasts, dilemmas, and disturbances, all witnessed or summoned by a narrator who offers unflinching observations of nature, scenes, and moods. In keeping with her first two collections, Doll God (Aldrich Press, 2015) and Kin Types (Finishing Line Press, 2017), Castle has woven family members and childhood memories into sometimes quiet, sometimes tumultuous present day reflections.

The quote by Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius introduces the concept of the great divide between the “rooted” and the “winged”: “What springs from earth dissolves to earth again and heaven-born things fly to their native seat.” Section I features imagery that elaborates on the predicament of being conscious of dualities, contradictions, and contrasts. The narrator in the opening poem, “Tuesday Afternoon at Magpie’s Grill,” as in many of the poems, notices the world both inside and outside, the “Dodger talk at the bar,” the shady sycamore tree outside, but “No matter what I notice/no matter what I record, I will never/capture the ease of wind-filled wings,” and there is the book’s theme as well as the narrator’s dilemma.

“Waterland,” a complex and tightly constructed poem of four six-line stanzas, offers the contrast again in a photo description of the narrator’s mother holding her as a newborn standing beside a lake, alongside images of star-birth, followed by stars seeing their reflections in the same lake: “Reflected in the lake below, the stars watch their lives.” Similar contrasts occur in “Your Foot Bone Connected to Your Heart Bone,” in the mention of possums, creatures of the earth, and crows, belonging to the sky, all embedded in memories of the family matriarchal history: “Being the daughter of a daughter, the girl/formed first in the grandmother, one/of many explanations for their bond.” Section I reveals glimpses of parents, grandparents, scenes from childhood, and questions. In “Gravity,” the title itself displays the narrator’s difficulty as she asks her grandfather, “Why hasn’t one of us learned to fly?/What keeps us pointed downward?” after mentioning, “We could puff into the blue like clouds.”

The idea that humans are confined to time and space is also embedded throughout Section II, and there are no apprehensible solutions. The narrator of “Behold the Needle,” finds that she cannot “take apart the earth beneath me/for the memories grow together/like moldy pages, impossible/to separate . . . .” She “cannot be only here and not/there and there at the same time.” Not only are we confined by geography, but we are constrained by the absolutes of nature within our families and in our minds. In a prose poem, “The Wildlife Photographer and the Big Kill,” the speaker recovers from a desert fever inside, her elderly cat beside her on the couch, when she spots a rabbit through the window, “alert for hunters, probability set against its survival to maturity,” but soon sees a bobcat ready to pounce on it. When she reaches the door, though, to shout at the bobcat, she is “now closer to the wild cat with its stoical hunger. The rabbit is out of view.” In this world to which we are confined, what is fatal for the rabbit is triumph for the bobcat, and the narrator feels a “hemisphere of mind” peeling away; “What’s left is raw and untroubled.”

Heavenly realms, such as the sky, clouds, and stars present a possibility for transcendence, but they too are marred by brutal realities, and earth’s exuberance provides the contrast, as in “April Things,” a poem that juxtaposes the “saguaro’s top blossom,” grinning “toward the sun,” and the “wisteria pregnant with blossoms” with “two birds of prey,” their “beaks glutted with hearts/gizzards, spindly legs dangling . . . .” Aside from the enviable feature of flight and the beauty of clouds in the heavenly regions, the two realms are not distinctively better than one another, as the nature of attachment combined with the reality of death permeates both.

Life events, family history, and memories have a stronger hold in Section III. “Into Pulp,” a poem in which the narrator stands beside a lake watching the “constantly moving water/stones and minnows distort into segments,” and recalls her grandparents, presents a remarkable image of the nature of memory when she thinks, “if I haul memory from this grave/the transmigration into pulp continues.” The speaker of “Finally Going to Tell You about the Staircase Ghost” says much the same thing when she describes the memory of giving her baby peaches only to discover that they were pears while washing out the can: “the membrane between here/and there can separate as an unexpected/wind swishes silk draperies apart.” No matter how shrewd the perception, understanding can be re-arranged and even undone.

Beyond conflicts in the natural order, and beyond the pain of memory, there is a type of anguish in just being human and having attachments to people, animals, and moments. “When I’m in Charge” explains the pain behind memory and life’s dilemmas with its ending lines:

We’re all safe in the future because

of what I’ve done, outlawing grief

and its wily predecessor love.

A tone of grief move through most of the poems in their presentation of people, moments, and scenes. They reveal the difficulties that life can hold and the emotional disturbance that accompanies memories, without lapsing into sentimentality or brazen nostalgia. For example, in “A Year in Bed, with Window,” she never explains why she is confined to the bed for so long but finds that nothing beyond the “edges/of the bed matters to me”:

Not the wind sifting through

the aspen leaves way up

there or the lizard sunning,

a bicyclist’s hair streaming

on her way to the market.

An even darker vision seeps out in Section IV in poems about old age, caregiving, hearing aids, and distressing memories. In “Meditation,” even if she might “be safe in my garden/with my mint-trimmed tea” the thoughts “come get me./They are relentless, insatiable.” They “come with their rank breath/when we’re desperate for sleep,” and “they watch/waiting for/that moment to slip up behind you” as in “Seekers.” The anticipation or pondering of transcendence diminishes, since “Even birds and bats fall to earth when/they die” in the poem, “The Purpose of Earth.” Also, “Golems rumble out of the earth but/we fail to recognize them as we crash/to the ground together.” The poems point to the suffering buried beneath all of life’s experiences and connected to the universality of death.

“Without Flight” is a splendid example of Castle’s poetic skill, especially her ability to describe actions and scenes with startling verbs. The speaker, looking out the window, sees a hawk on the ground eyeing a dove chick in a nest; she and her husband have already observed “two hawks soaring, then circling, and swooping” while “Owls stand sentinel at the roof edge.” In this world of predators, “The bobcat/and coyotes target and strike their own prey.” The fact that the hawk is injured, unable to fly, and is “motionless” on the concrete shifts the tone and outcome of the poem; she remembers “hawks heavy-winged above me,/the gliding and patterns and power in the sky”; but now, “To catch her without flight is the catastrophe.” There is danger in being either the rooted or the winged.

In “How They Fall,” the speaker is now, like the hawk without flight, “without voice.” She sleeps “without landing,” and has “knobby scars/where the wings once grew as spindles.” She says, “What falls away is always.” The pain of becoming conscious, aware that predators pose dilemmas but that they too are susceptible to the ravages of time, is reminiscent of Robinson Jeffers and his poems about predatory birds.

The agony of decay, of gravity, of attachment and loss, of aging and caring for the aged, are all currents in Rooted and Winged. The world Castle has invoked is vibrant and intense, threatening and consoling, exquisite and dangerous. Nonetheless, despite the tormenting possibilities, and despite the fact that the “last star” can “darken/like an executioner’s hood,” as in the final poem, “After Darkness,” we might find “long after, a flicker from the pile./We bring our efforts to the task.” Her poetic efforts, like the woman sitting at Magpie’s Grill in the opening poem, have given her and her readers, if only for a fleeting few moments, the ease of wind-filled wings.